This post was inspired by a patient I took care of on a Cardiology rotation as an off-service EM intern. I find that much of my learning now that I am no longer a medical student is based in those that I care for, although I’m not sure the Cardiology team was as enthusiastic about the chemical structure of sulfamethoxazole as I was.

An elderly woman with heart failure, kidney disease, vitiligo, and a sulfa allergy was admitted with progressive shortness of breath and pedal edema, consistent with a heart failure exacerbation. Ethacrynic acid, her home loop diuretic, was unable to be titrated to a dose sufficient for diuresis. She was then transferred to the Cardiac ICU for monitored desensitization to furosemide.

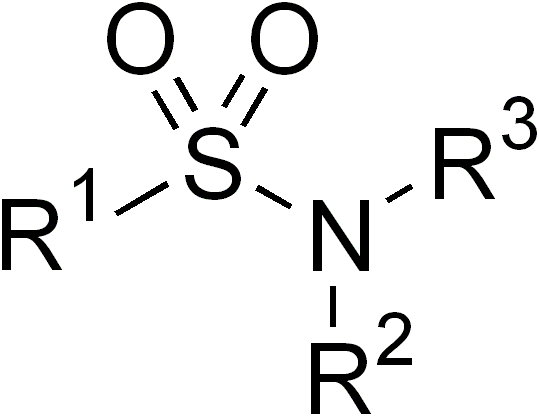

First, what does the “sulfa” in sulfa allergy refer to? It is typically used as shorthand to refer to sulfonamide drugs, which all share a characteristic backbone (R-SO2-N-R’,R”):

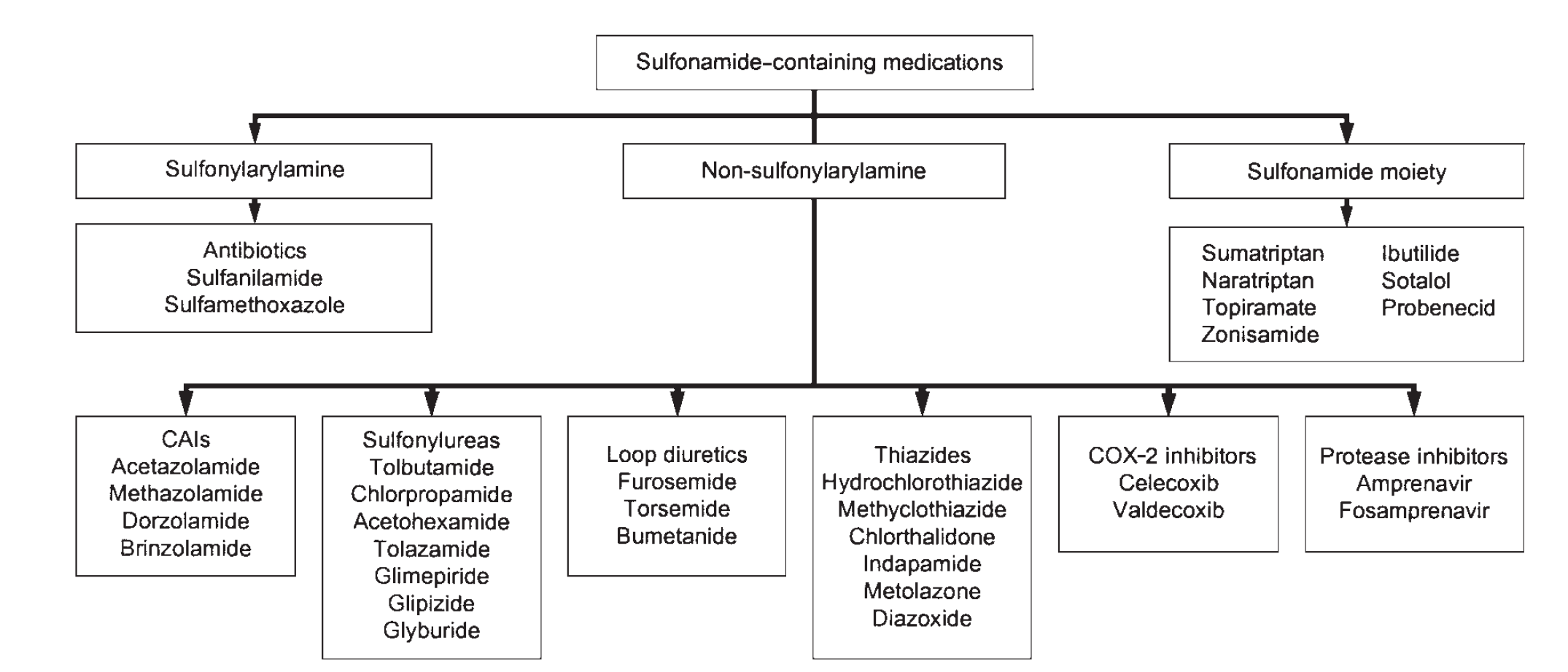

Sulfonamide allergy is perhaps the second most common listed allergy I see behind penicillins, a fact that borne out in the literature as approximately 3-6% of sulfa antibiotic courses are complicated by a drug reaction.1 In nearly all charts I’ve seen, the culprit drug was a sulfonamide antibiotic (typically sulfamethoxazole in TMP/SMX, also known as Bactrim, Septra, or Co-trimoxazole). Are these patients forevermore banished from all drugs containing the sulfonamide moiety? This is pretty constricting, given the list of sulfonamide nonantibiotics in common use, some of which are widely known (furosemide, sulfonylureas) and some of which are more surprising (thiazides, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, COX-2 selective NSAIDS):2

Of the 33 drugs listed above, more than half contain a warning or contraindication related to use in patients with a sulfonamide allergy in their manufacturer’s package insert.2 The concept of sulfa-drug cross reactivity is so entrenched that we even have a dedicated furosemide desensitization protocol on hand for cases like this.

As a preface to understanding why the concept of a broad sulfonamide allergy is silly, we have to quickly review adverse drug reactions in general. There are two main categories of drug reaction: type A and type B.3 Type A are directly related to a drug’s pharmacology and are often both predictable and dose-related. They are not immunologic. Type A reactions for TMP/SMX, for example, include blood dyscrasias from folate deficiency (expected given the anti-folate mechanism of action), hyperkalemia (from TMP’s inhibition of ENaC in the distal tubule, similar to amiloride), or hypoglycemia (sulfonylureas were developed from sulfanilamide).4

Type B reactions are the classic “hypersensitivity” reactions we are taught in medical school. They are immune-mediated and further subcategorized into one of four types using the Gell-Coombs system. Immediate hypersensitivity (type 1), is IgE mediated and ranges in presentation from urticaria to anaphylaxis. It occurs when an antigen binds to and cross-links IgE molecules on mast cells and basophils, yielding subsequent histamine release. Crucially, this binding and cross-linking is extremely specific: the IgE recognizes only one small part (the “epitope”) of an often-larger antigen. Keep this concept in mind for later.

Cytotoxic hypersensitivity (type 2), also known as antibody-dependent hypersensitivity, occurs when IgG or IgM antibodies recognize a particular antigen on a host cell, leading to the inappropriate destruction of that cell. This is often drug-mediated, where the drug acts as a hapten (a small molecule that is only immunogenic when carried by or bound to a larger molecule, often a protein). Hapten-coated cells can then be targeted by IgG or IgM. One common example of this is penicillin-induced hemolytic anemia.5

Immune-complex hypersensitivity (type 3) is the result of drug-IgG complex formation, which can then deposit into tissues and cause an inflammatory response. Serum sickness, a syndrome with protean manifestations (fever, arthralgias, organ dysfunction) is a type 3 hypersensitivity reaction that can occur after sulfonamide antibiotic exposure and, as we will discuss, is instigated by downstream metabolites of the parent antibiotic.

Finally, the most common hypersensitivity reaction observed in response to sulfonamide antibiotics is delayed-type (type 4). This occurs when antigen presenting cells (APCs) present an antigen to Th1 cells via their major histocompatibility complexes (MHC). The Th1 cell then releases multiple cytokines and other immune mediators to activate downstream effectors of inflammation like macrophages or cytotoxic T-cells. These hypersensitivities run the gamut from benign exanthematous rashes to severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) like Stephens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), or drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).6 Similar to other hypersensitivity reactions, the immune system is recognizing a specific moiety on the antigenic molecule, and other molecules (drugs, in this case) lacking these moieties are not at risk for provoking this response.

Now that we have that out of the way, how exactly are sulfonamide antibiotic hypersensitivity reactions generated? We can start with IgE-mediated hypersensitivity. Which part(s) of SMX are immunogenic? What is the epitope that the body is raising IgE against? If we look again at the SMX molecule, there are two groups unique to it and other sulfonamide antibiotics.

The first is an arylamine group at N4, shown in the blue box. As a reminder, arylamines are simply an amine (the nitrogen containing group shown) bonded to an aryl (benzene-derived) group. This particular arylamine has the amino group para to the benzene ring attachment. The second group unique to sulfonamide antibiotics, in red, is a heterocyclic N-containing ring, bonded to the N1 nitrogen of the central sulfonamide moiety.7

It is this heterocyclic N1 group that is the immunogen recognized by IgE, which has been shown elegantly both in vivo and ex vivo.7 IgE has never been shown to bind to the sulfonamide group, which is the only portion sulfonamide antibiotics share with their nonantibiotic cousins. For reference, the structure of furosemide is reproduced below: notice the absence of both an N1 heterocyclic ring or an N4 arylamine.

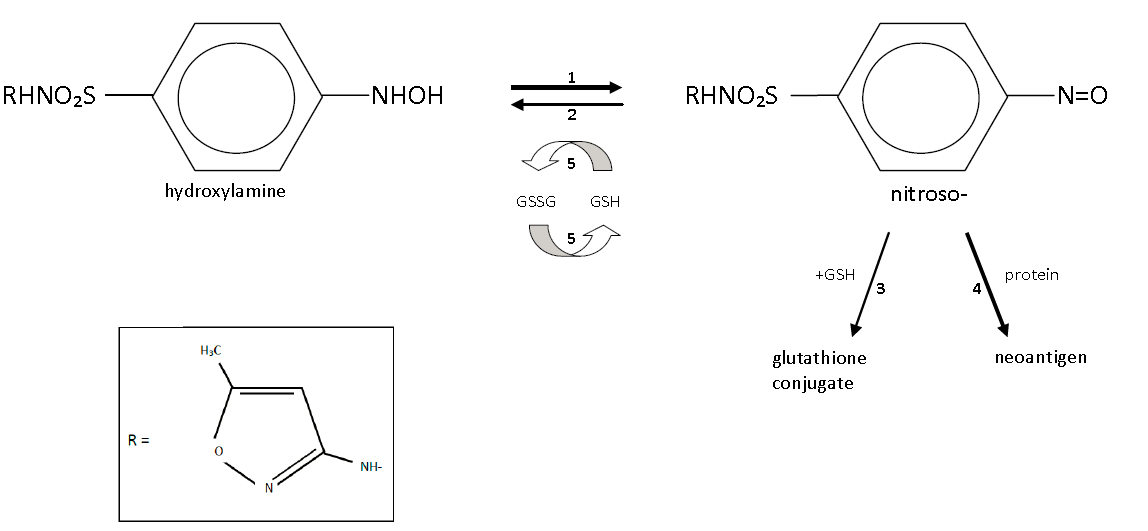

However, it is the non-IgE hypersensitivity reactions that are the most worrisome with SMX and potentially with other sulfonamides. As we reviewed above, there are multiple potential non-IgE immunogenic mechanisms for toxicity in sulfonamides: SMX or its metabolite might bind to a native protein, eliciting either a cellular or antibody-mediated response (type 2). Or, SMX (or metabolite) might directly bind to a cellular protein (haptenation, type 3), leading to direct cytotoxicity or immunogenicity. Finally, SMX (or metabolite) might produce a T-cell immune response directly (type 4).

The common mechanism behind the non-IgE immune responses seen from SMX involves its metabolism. It is not the parent compound per se that evokes the toxicity, but downstream reactive metabolites that lead to haptenation and direct cytotoxicity or a harmful T-cell immune response. We will explore some of the specifics of this below.8

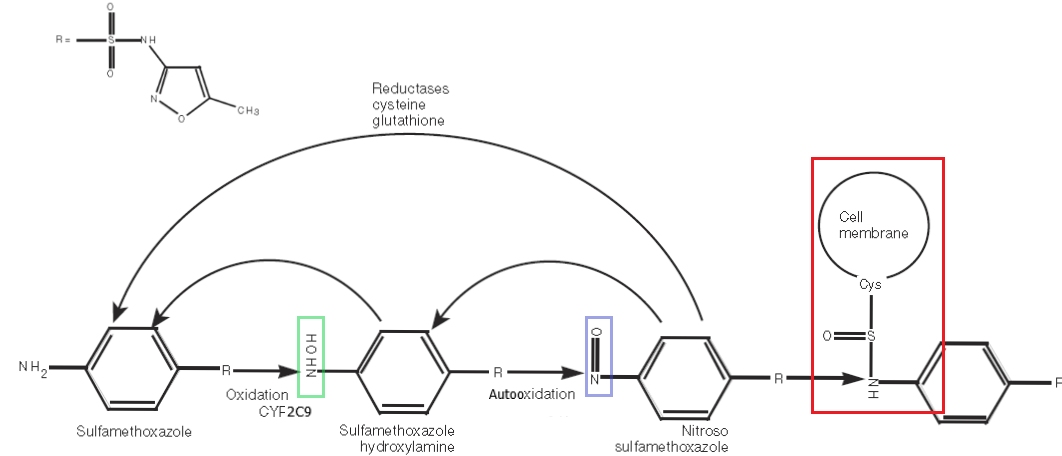

The metabolism of SMX is somewhat complicated and most is not relevant to the topic at hand. Suffice it to say, approximately 10-20% of SMX is oxidized at N4 by the highly polymorphic CYP 2C9 enzyme to the hydroxylamine intermediate. This intermediate has been shown to be present in higher concentrations in the urine of those with hypersensitivity to SMX and is modestly reactive.9 However, it is the autooxidation of this hydroxylamine to a [-nitroso] intermediate that has the potential to wreak havoc in our bodies. The [-nitroso] compound readily forms protein adducts that can be either directly cytotoxic or, more often, highly immunogenic.8 The nitrososulfonamide is thought to be responsible for both the complex-mediated serum sickness-type reactions and the delayed SCAR dermatopathies that can be fatal.7

The extraordinary polymorphism present in the CYP enzymes (particularly 2C9) allows us to understand why millions of people take TMP/SMX without incident each year. In the primary metabolism of SMX, the proportion of the drug that is acetylated and harmlessly secreted into the urine is between 45-70% and depends on the 2C9 alleles present. More active 2CP enzymes (e.g., CYP 2C9*1/*1) generate more reactive N4 hydroxylamine, which yields more of the nitrososulfonamide. The NAT2 enzyme, of “fast-” and “slow-acetylators” fame from intro pharmacology courses, is responsible for the acetylation of the toxic N4 hydroxylamine compound into one that is harmless and renally excreted. Thus, “slow acetylators” (NAT2*5B/*5B homozygotes) shunt more of the hydroxylamine into the reactive [-nitroso] intermediate, whereas “fast acetylators” clear the hydroxylamine more efficiently.9

Finally, the metabolism of the nitrososulfonamide is heavily influenced by the redox state of the cell: the [-nitroso] molecule can be reduced back to the less reactive hydroxylamine by glutathione reductase but requires a favorable ratio of reduced-to-oxidized glutathione. Recurrent redox cycling of this reaction or any other sort of oxidative stress leads to a marked decrease in the normally favorable reduced:oxidized glutathione ratio. HIV, in particular, leads to a tremendous oxidative stress via the indirect inhibition of superoxide dismutase by the Tat viral protein, which depletes reduced glutathione and is one reason why those with high-VL HIV disease have a tremendous proclivity to hypersensitivity reactions from SMX (as much as 40% in some studies!).3

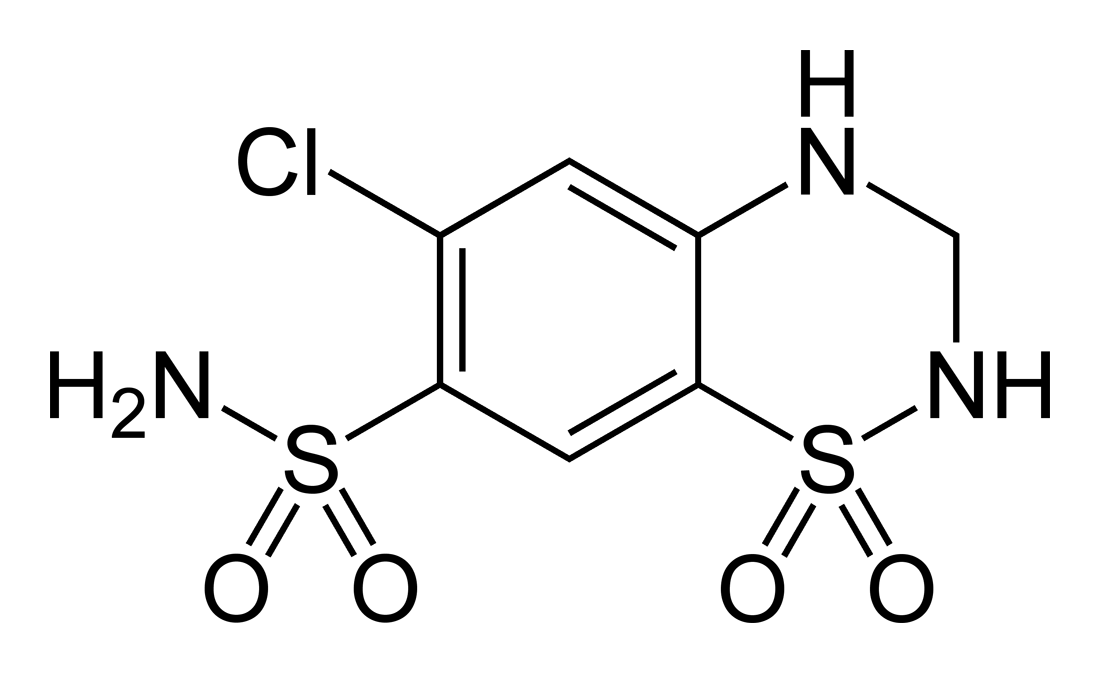

So, then, to return to our original question: is there a credible basis for cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics? The structural requirements for these reactions are 1) a heterocyclic N1 group (for IgE mediated) or 2) a primary arylamine with amino group para to the benzene ring attachment (for non-IgE mediated hypersensitivity). Does furosemide, reproduced above, have either of these groups? No! Keen readers, however, might notice that furosemide (similar to SMX) is a sulfanilamide – it contains an N4 arylamine. However – and this distinction is important – it is a secondary arylamine (i.e., the nitrogen is bound to one hydrogen and two functional groups), rather than a primary arylamine (the nitrogen is bound to two hydrogens and one functional group). It is the primary arylamine that can undergo oxidation by 2C9 and further autooxidation into the potentially harmful [-nitroso]. How about HCTZ (below)?

No again – while the sulfonamide moiety remains, the N1 heterocyclic ring and the arylamine group are absent, and HCTZ does not evoke the same immune response SMX does. Other than the antibiotics, no other sulfonamide xenobiotics contain the necessary primary arylamine, which therefore means they cannot produce the reactive [-nitroso] intermediate essential for hypersensitivity in the context of a susceptible host. It is the stereospecific formation of the cytotoxic or immunogenic hydroxylamine and nitrosamine intermediates rather than the initial sulfonamide group causing the trouble.

This pharmacology is all well and good, but to use a scientific cliche, “In God we trust; all others must bring data.” Thankfully, we have data ranging from massive retrospective cohort studies to smaller, prospective trials of individual patient challenges with potentially cross-reacting drugs.

The most prominent reference here comes from the NEJM in 2003.11 It is not perfect science, but is the largest population-level study we have. Strom et al searched the UK

General Practice Research Database (encompassing >8 million patients) from 1987 through 1999. The population they studied included patients that were prescribed a sulfonamide antibiotic and, >60 days later, were also prescribed a nonantibiotic sulfonamide. Their study and comparison groups were patients who

“contacted their general practitioner with a condition compatible with an allergic reaction within 30 days after receiving a sulfonamide antibiotic.” Sound shaky? It is, especially when you see some of the ridiculous “allergies” listed in the EMR. The control group were patients who did not report an allergy after the antibiotic.

The primary outcome was then patients who, within 30 days of receiving their nonantibiotic sulfonamide, was diagnosed with an allergic condition attributable to that drug. This has slightly more face validity to it, as it required an in-person consultation, but is still unfortunately nonspecific. For what it’s worth, they used two definitions of hypersensitivity: narrow, e.g, urticaria, anaphylaxis, erythema multiforme, and broad, which also included asthma, eczema, and unspecified adverse effects of a drug. That being said, they report their initial results with the broad definition and state that, without showing their work, their analyses “were not substantively different” using the narrow definition, so, again, these data are not perfect.

What they found was interesting: the odds ratio for an allergic reaction after a nonantibiotic sulfonamide for a patient with a history of sulfonamide hypersensitivity was 6.6 (2.8 when adjusted for multiple confounders). Not looking good for this tale of non-reactivity we are telling, right? Well, they also found that patients with a history of sulfonamide hypersensitivity had an odds ratio of 7.8 (3.8 adjusted) for experiencing an allergy to PENICILLIN compared with those who did not have a sulfonamide hypersensitivity history. Moreover, when they compared patients with a sulfonamide allergy to those with a penicillin allergy, 9.1% of “sulfa” allergic patients experienced a reaction to a subsequent nonantibiotic sulfonamide compared to 14.6% of those with a history of penicillin allergy.

The authors make an excellent point, which I will reproduce below:

Our results suggest that, although allergy to a sulfonamide antibiotic is indeed a risk factor for a subsequent allergic reaction to a sulfonamide nonantibiotic, a history of penicillin allergy is at least a strong a risk factor. The association initially seen in the primary analysis with the sulfonamide nonantibiotics might be explainable by a general predisposition to allergic reactions among certain patients rather than a specific cross-reactivity with drugs containing the sulfa moiety.

It is clear that there exists a subset of patients with a hyper-allergic phenotype: for unclear reasons (MHC polymorphisms? variations in drug metabolism? variations in T- or B-cell function?) some people easily develop multiple, independent allergies. This does not mean that PCNs cross-react with sulfonamides – in fact, we know that not to be true when we expose one of them immune cells sensitized to the other – but that in your pan-allergic patient, caution is warranted when initiating new drugs.

How did this medical myth become so entrenched? Surely there must be significant data to suggest cross reactivity. In short, no, there are not. A recent review of all reported cases from 1966 to 2011 found a total of 9 case reports of possible sulfonamide cross reactivity, some of which had extremely questionable verification of hypersensitivity.7 A recent, updated review, which includes additional sulfonamides that have been recently approved, did not yield any additional cases.3 In fact, a cursory search of PubMed reveals multiple dogmalytic reviews of the topic, all of which come to the same conclusion: no credible evidence for broad cross reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and nonantibiotic sulfonamides exists.2, 3, 7, 8, 1o

This misconception has been perpetuated since the first case report of cross-reactivity (acetazolamide and SMX) was published in 1955.12 Its genesis is in early prescribing information, when these sulfonamide derivatives were first being developed. Before we understood haptegenicity or the stereospecificity of both IgE and non-IgE mediated hypersensitivities, it was routine to include a general prescribing warning about drugs containing a sulfonamide group. This prescribing information has never been updated, and even newer drugs include the boilerplate contraindication. The reasons behind this are likely multiple, one being that there is little to no incentive for manufacturers to conduct systematic allergy challenges in this potentially high-risk group of patients.

Multiple small series have prospectively challenged purportedly sulfonamide hypersensitive patients with other sulfonamides, with no cases of hypersensitivity occuring.3 It is time to put this myth to bed.

What happened to the patient in our introduction? I gave my impassioned defense of the sulfonamide loop diuretic, but an off-service intern unfortunately holds little weight and our patient was de-sensitized to furosemide for the third or fourth time. It was, of course, successful. My leading theory as to why our patient would intermittently develop these idiosyncratic drug rashes is that she was one of the pan-allergic types I mentioned above: she already had vitiligo, an cutaneous autoimmune disease likely mediated by T-cells, and what are these delayed-type drug hypersensitivities if not T-cell mediated dermatopathies? This is borne out of least one paper I have read, suggesting that severe T-cell mediated allergies can be predicted in part by models including disease like vitiligo.13

I look forward to any feedback or discussion on this post – comment below, or reach out to me at @pfehlers on Twitter.

Stay curious, everyone!

EDIT: I’ve added an update to address questions I’ve gotten about both darunavir and dapsone. See my comment below!

References:

- Bigby M, Jick S, Jick H, Arndt K. Drug-induced cutaneous reactions. A report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program on 15,438 consecutive inpatients, 1975 to 1982. JAMA. 1986 Dec 26;256(24):3358-63.

- Johnson KK, Green DL, Rife JP, Limon L. Sulfonamide cross-reactivity: Fact or fiction? Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(2):290-301. doi:10.1345/aph.1E350

- Dorn JM, Volcheck GW. Sulfonamide Drug Allergy. In: Drug Allergy Testing. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports; 2017:145-156. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-48551-7.00014-6

- Velázquez H1, Perazella MA, Wright FS, Ellison DH. Renal mechanism of trimethoprim-induced hyperkalemia. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Aug 15;119(4):296-301.

- Riedl MA, Casillas AM. Adverse drug reactions: types and treatment options.Am Fam Physician. 2003 Nov 1;68(9):1781-1791

- Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet. 2017 Oct 28;390(10106):1996-2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30378-6.

- Wulf NR, Matuszewski KA. Sulfonamide cross-reactivity: Is there evidence to support broad cross-allergenicity? Am J Heal Pharm. 2013;70(17):1483-1494. doi:10.2146/ajhp120291

- Brackett, CC et al. Likelihood and mechanisms of cross-allergenicity between sulfonamide antibiotics and other drugs containing a sulfonamide functional group. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(7):856–870

- Lehmann, DF. The Metabolic Rationale for a Lack of Cross-reactivity Between Sulfonamide Antimicrobials and Other Sulfonamide-containing Drugs. Drug Metabolism Letters. 2012;(1):129-133

- Shah TJ, Moshirfar M, Hoopes PC. “Doctor, I have a Sulfa Allergy”: Clarifying the Myths of Cross-Reactivity. Ophthalmol Ther. 2018;7(2):211-215.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of Cross-Reactivity between Sulfonamide Antibiotics and Sulfonamide Nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(17):1628-1635. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022963

- Mosely V, Baroody NB. Some observations on the use of acetazolamide (“Diamox”) as an oral diuretic in various edematous states and in uremia with hyperkalemia. Am Pract Dig Treat 1955;6:558-66.

- Michels AW, Ostrov DA. New approaches for predicting T cell-mediated drug reactions: A role for inducible and potentially preventable autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Aug;136(2):252-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.024.